The season is over. The riders and teams bring the curtain down; ready to start over with a clean slate as they await another season full of renewed illusions and new material. The used motorcycles are left aside. Of course, this can be afforded by the wealthiest because there is a lot of private training in the lower categories that often recycles and adapts the bikes from one season to the next. Everyone would like a new motorcycle every year, but that’s not always possible. In MotoGP, it’s different because it is a category subject to constant renewal. What is the destination of MotoGP motorcycles once a championship ends?

In the past, the official material from the previous season was usually recycled, sold, or leased to private teams. Many other times, the motorcycles that weren’t going to be used anymore became show models in motorcycle expos, which sometimes gave rise to a certain guile.

The most notable case was the one of a Honda RC166 unit, the six-cylinder 250cc with which Mike Haliwood was 250cc champion in 1966 and 1967. In February 1968, Honda announced its withdrawal from Grand Prix racing and offered Haliwood a substantial contract to also leave World Championship racing, while also offering him various units of his champion motorcycles to compete in international events, with which he earned significant profits. But in 1969, those prodigious machines ended up tossed aside. Or at least, that’s what they thought in Japan…

One model ended up with Honda Germany as a show bike for European motorcycle expos. Then, without anyone knowing very well how, that six-cylinder 250cc appeared in the 1969 German Grand Prix trainings in Hockenheim, driven by Gerhardt Heukerott, an unknown, independent German rider, who managed to persuade those responsible at Honda Germany to give him the bike.

The adventure ended badly because such a sophisticated motorcycle needed delicate maintenance and ended up suffering a malfunction that didn’t allow it to start the race. Afterwards it was lost track of, like so many motorcycles from the time. Some can be seen at the Twin Ring Motegi Honda Collection Hall; others have ended up in the hands of collectors.

Auctions and collections

Sometimes the most curious things would happen with racing motorcycles. A few months ago the Benelli 250/4 with which Kel Carruthers won the 250cc World Championship in 1969 was auctioned. The history of this motorcycle is a most bizarre one. This was the last season that that mechanical configuration was able to be used due to a change in regulations, therefore the destination of the motorcycle was the private collection of the Benellis.

However, when the brand was acquired by the De Tomaso Group in 1972, Marco Benelli, one of the children of Giuseppe Benelli, founder of the company, took out the engine from the motorcycle to use it in his own street bike… Unheard of. Subsequently, all the material, engine, and chassis, was recovered by Giancarlo Morbidelli and the motorcycle was restored in the Morbidelli Museum, but after its dismantling two years ago, it ended up auctioned at Bonhams, one of the most well-known auction houses in the world.

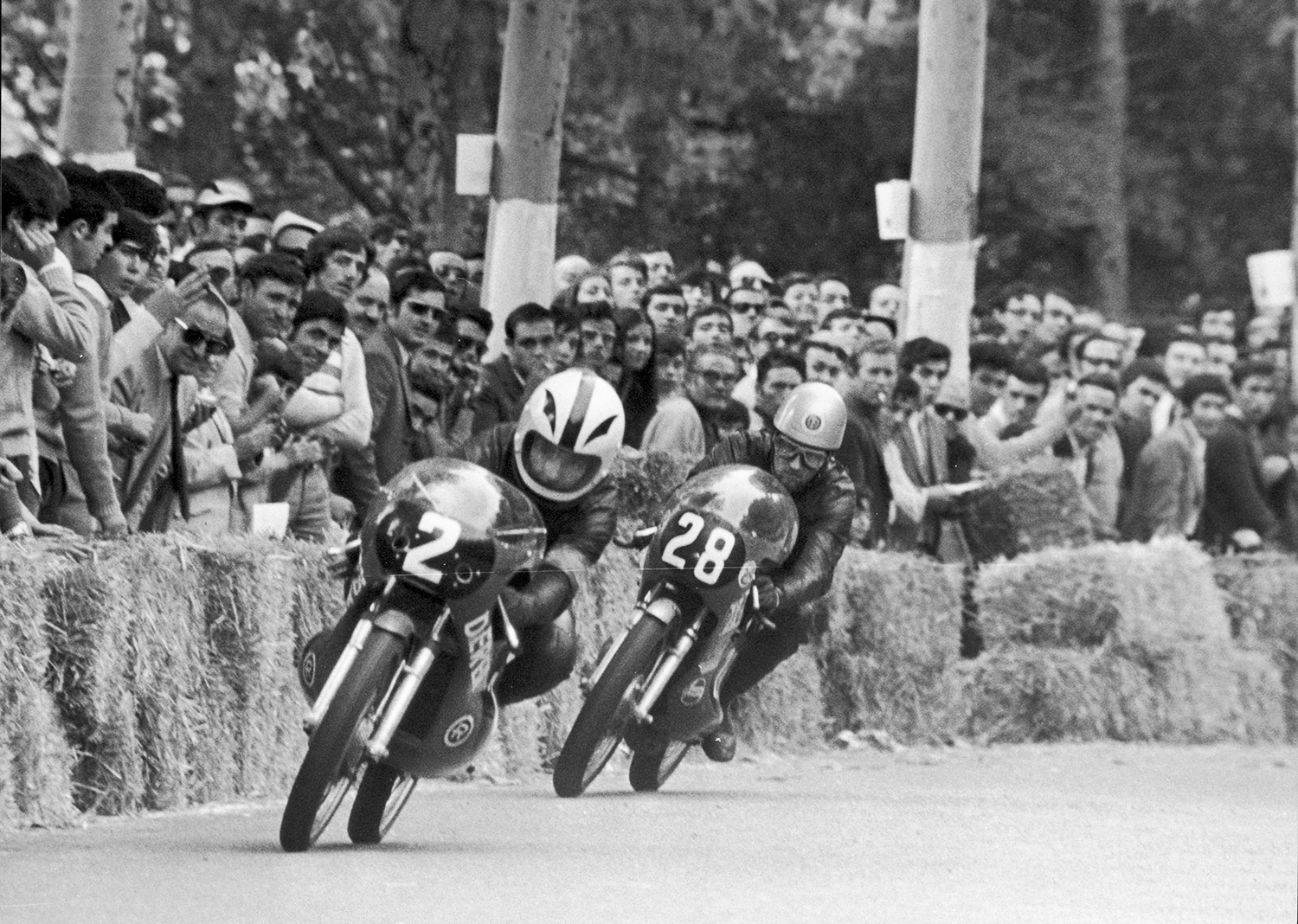

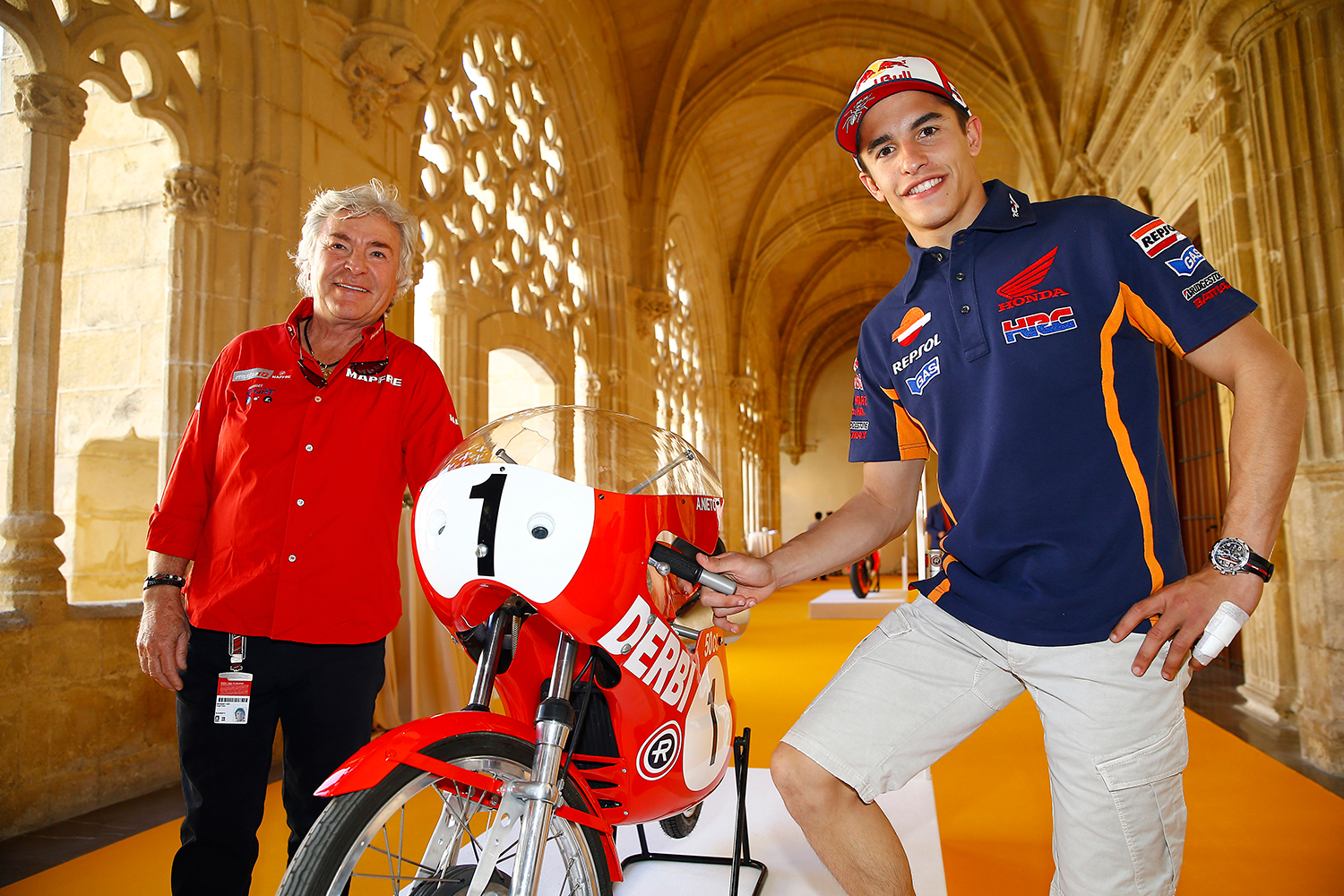

It was a habit of Ángel Nieto, sometimes by contract, to keep champion motorcycles. He always kept a unit of the motorcycles that he won with, creating a valuable collection. Even on one occasion, he convinced owner Commendatore Minarelli to let him keep one on the very podium after he became champion. “I knew that if I asked him at that moment, he would not be able to refuse me,” Nieto confessed on one occasion. And that was that. The 125cc Minarelli is one of the joys of our much-missed “12+1” collection.

Currently in MotoGP

There were also cases where after keeping some units for different uses, other models were destined for the scrapyard, although this practice is no longer used. These are not the times to throw anything away, and cost savings are just as important as good design. One must bear in mind that each rider has two units in MotoGP –not like in Moto2 and Moto3, where they only have one motorcycle due to budget issues –, and that on top of the riders that compete in the championship, all manufacturers have a test team that also has a variety of material and works with different units: last season’s bikes, current bikes, prototypes, etc.

For example, at Honda, one season’s bikes serve as a basis of evolution for the following season, and work is carried out on them. In the past, these motorcycles were used as material for the brand’s satellite team, but as of last season this isn’t the case because Honda is building identical units both for the official team as well as the satellite team. The motorcycles that are no longer used have different destinations: they are sent to Japan for different events or are delivered to sponsors, such as Repsol, whose main headquarters in Madrid boasts a luscious collection of champion motorcycles from the 500cc World Championship and MotoGP.

At Ducati, they make the most of a lot of material to prepare the following season’s bike. As we can see, the service life of a motorcycle can easily extend over two or even three seasons depending on the needs of the manufacturer and its commitments to its satellite teams.

But there comes a time when the motorcycles stop being used. What happens to them then? “It depends on the leasing contracts with independent teams,” Ducati says. “Some motorcycles are upgraded and are reused for the following season, others are sold to collectors, and one always ends up in the Ducati Museum.”

And when the service life of motorcycles reaches its end, what happens to those? “Some of them become test team motorcycles, others are destined for the dyno, and others become show bikes”, states Ken Kawauchi, technical manager of Suzuki in MotoGP. Ultimately, everything is made the most of.

At the end of 2018, KTM had an interesting initiative: sell two units of its RC 16, its MotoGP bike. It was the first time that a manufacturer put two genuine MotoGP motorcycles on public sale. In the past, Ducati had already made some of its bikes available to collectors, but KTM gave a new dimension to selling a racing bike in such a public and open way to anyone who could afford it. And not just any bike, none other than a MotoGP one. The offer also included a complete set of equipment signed by the rider (helmet, suit, gloves, and boots) and the chance to share a Grand Prix with the team in the same box. And all that for “only” 250,000 euros.

It is certainly a significant figure, but at least it is a first practical reference to measure the value of these unique and exclusive museum-worthy motorcycles, which would not deserve any less noble destination than this one.

Join Us

Join Us  Join Us

Join Us